Testing

LexaGene’s new automated testing platform

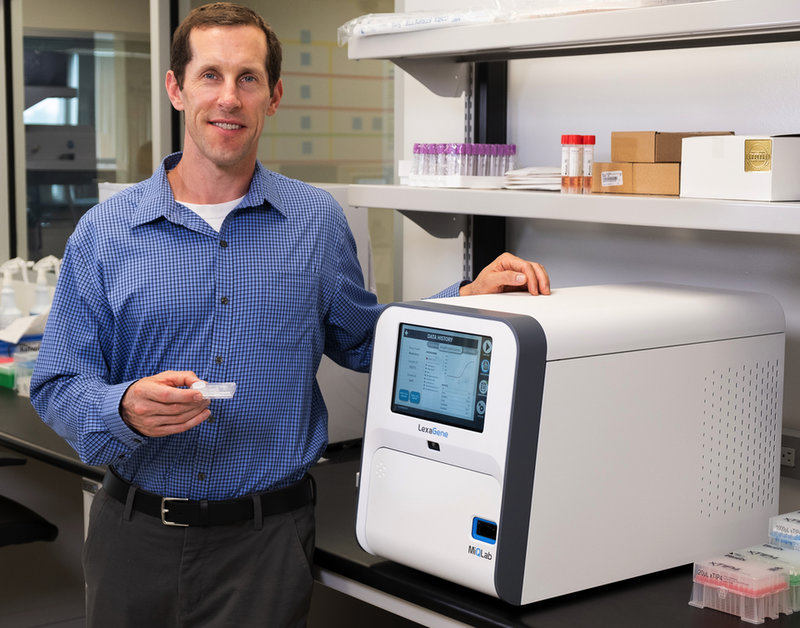

Massachusetts-based LexaGene is preparing to launch MiQLab, the company’s flagship product, which provides automated pathogen testing in one platform. The unit can screen samples for up to 27 different targets at once and has been designed in an open-access way, so that users can customise their own tests. Abi Millar spoke to the firm about the launch of this new tech and how it could change diagnostic procedures.

S

ince the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, diagnostics have rarely been out of the spotlight. A number of coronavirus tests have hit the market, many of them beleaguered by problems relating to sensitivity or specificity. Speed has also been an issue, with the typical polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test (considered the gold standard testing platform for viruses) taking 12-24 hours to return results.

For Massachusetts-based LexaGene – which has a new diagnostic technology pending US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval – there is a clear gap in the coronavirus testing market. MiQLab, its flagship product, fully automates the PCR testing process. It can also screen samples for up to 27 different targets at once, returning results within an hour. This means it can be used to test not just for Covid-19, but also for differential diagnoses such as flu.

“The instrument will be able to test for a wide range of respiratory viruses, so when somebody comes in with symptoms, there's a higher probability of telling them exactly what caused the illness,” says Dr Jack Regan, LexaGene’s founder and CEO. “All of a sudden you have a tremendous amount of confidence telling the patient, listen, you have this other pathogen. It's not coronavirus, you do not need to self-quarantine.”

As well as Covid-19 testing, Regan expects the technology to make waves in veterinary medicine, open-access testing (in which users can customise their own tests) and even food safety. He adds that the instrument will have exceptional sensitivity and specificity.

“Because we view LexaGene as offering a premium product, we want to hit the market with something that is effectively considered the Mercedes Benz of the human clinical diagnostic space,” he says.

LexaGene’s story to date

Regan did not start out by thinking about Covid-19 specifically. A virologist by training, he began his career at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory before moving on to various biotech companies. Between 2008 and 2010, he invented the technology that is now being commercialised as MiQLab.

He founded LexaGene in October 2016 with a view to developing this technology. With two patents to its name, and not much else, the company immediately went public on the Canadian stock exchange.

“We started with two pieces of paper effectively and had to develop this brand-new technology with very limited financing,” says Regan. “Over the next year and a half, we started product development and tried to generate interest among investors, even without a working prototype. After we had raised enough money, we leased our own space north of Boston, hired our own staff and started developing the product in-house.”

We started with two pieces of paper effectively and had to develop this brand-new technology with very limited financing.

Following numerous capital raisings (including a C$6.64m raise last October), LexaGene was able to place a prototype in the hands of potential customers. The company conducted clinical trials at a veterinary hospital, a human clinical laboratory and a reference lab that looked at agricultural pathogens and food safety.

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused some delays, with supply chain issues hindering the delivery of several key components. However, these issues are now resolved and MiQLab is moving steadily towards its launch date.

“We started designing our commercial systems last winter, and we're in the process of validating those in house,” says Regan. “We’ve launched our early access programme and we anticipate shipping units for that programme before mid-November. We also expect to be starting our FDA study for Covid-19 before the end of the year. It’s going to be a very exciting time for the company, pushing our technology out into the field.”

MiQLab is fully automated, reducing complexity for the end user. Credit: LexaGene

How MiQLab works

The technology is a form of ‘syndromic testing’, in which a single test is used to screen for a large number of pathogens or genetic targets.

“How it works is an individual loads a sample from the patient into a single use disposable cartridge, which is designed to purify the genetic material and remove any inhibitors that might stop the critical reaction from happening,” says Regan. “Then we assemble a series of PCR reactions, including controls that make sure the instrument is performing as it should.”

While the instrument takes over an hour to process the sample, it requires less than a minute hands-on time.

While there is nothing special or proprietary about PCR tests per se – the majority of labs can perform them – MiQLab is fully automated, reducing complexity for the end user. You simply load your chemistry into the tiny vials, enter the patient sample ID, hit go and the instrument does the rest.

“If you were to do PCR in a lab, you’d need three critical aspects – you’d need to purify the genetic material, you’d need to assemble the test and you’d need to amplify and analyse the data,” says Regan. “We do all that in a single instrument, completely hands free, which frees up a ton of labour time. While the instrument takes over an hour to process the sample, it requires less than a minute hands-on time.”

Uses in the vet space

Asked how MiQLab differs from existing diagnostics, Regan says it varies between customer groups. Within veterinary diagnostics, the current standard is shipping a sample to a reference lab and putting it through culture. This returns an answer to the vet within three to five days.

“In this case, we're competing against culture, and the business model of shipping a sample to a reference lab,” he says. “In the vet space, there really is no competition from automated PCR.”

We're competing against culture, and the business model of shipping a sample to a reference lab.

The technology will be launched in veterinary diagnostics before it’s approved for human applications. This is partially due to lower regulatory requirements, but also because being in the vet space first will allow the company to generate extra data.

“Our technology is going to go through improvements as the months and years go by,” says Regan. “It's easy for us to roll those improvements to the vet market, whereas in the human clinical market, once you’re through the FDA, everything is locked down or frozen. This is one of the reasons why we're pushing the FDA trial back until the end of the year – we want to feel comfortable that we’re at a good stage to go to the FDA, and are providing the best possible technology to the field.”

The technology will be launched in veterinary diagnostics before it’s approved for human applications. Credit: LexaGene

The potential within human clinical diagnostics

Within human clinical diagnostics, there are already some platforms out there that do automated PCR. However, MiQLab goes further in that it is open access and promises very high levels of accuracy.

“Not all PCR tests themselves are equivalent – they all have different sensitivity and specificity because of the quality of their sample prep, the quality of the assay design and also how fast they're pushing the chemistry. These all make a difference to how sensitive the reaction is,” says Regan. “The open access feature is completely unique, and we're really excited about the prospects for the company moving forward.”

Not all PCR tests themselves are equivalent – they all have different sensitivity and specificity.

LexaGene expects to submit to the FDA by the end of January and hopes to be on the market for coronavirus testing by February. The product will launch in the United States and Canada to begin with, before pursuing a CE mark.

And Covid-19 testing is really only the beginning. In the event of future infectious disease outbreaks, the instrument can be rapidly configured to detect novel pathogens (within a week of its genome being sequenced). This should prove a useful tool for halting the course of pandemics.

“People can get very myopic about one market, and obviously, people are very focused on the coronavirus market,” says Regan. “But there are many other markets that have a need for automated pathogen detection. Our goal is to make the technology smaller, cheaper, faster and more widespread across all these different market verticals. We have big plans for the company and feel like we have a technology that is needed in the marketplace.”