Virtual Reality

Virtual pain relief: could VR start a rehab revolution?

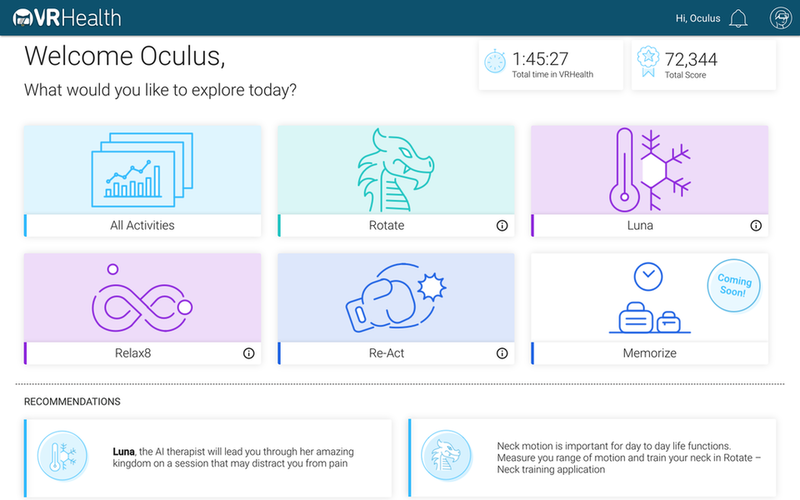

Israeli tech firm VRHealth is aiming to push forward the use of virtual reality in pain management, physical and cognitive therapy and other areas. With VR’s role in healthcare growing, could the technology provide new and effective remote therapy options, and even offer a solution to the opioid crisis? Chris Lo investigates.

Image courtesy of: VRHealth

A

lthough virtual reality (VR) in various forms has been rattling around the consumer and industrial markets for several decades, the genesis of the 21st century resurgence lies with tech firm Oculus VR’s 2012 Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign for the Oculus Rift, a VR headset designed for ultra-immersive videogames, which sparked a wave of consumer VR tech. The Kickstarter eventually raised $2.4m, nearly ten times its original $250,000 goal, and two years later the company was acquired by Facebook for $2.3bn.

Since then, there has been a startling transformation in the VR market. The ongoing refinement of VR headsets has opened up routes to a list of applications far broader than gaming and entertainment, from virtual training to immersive engineering and design systems.

VR’s role has been growing in various facets of the healthcare industry, as demonstrated by the growing use of the technology – along with augmented reality – to create cost-effective and repeatable training courses for surgeons. In physical and cognitive therapy, too, VR shows great promise.

It’s in the realm of ongoing therapy and rehabilitation that VRHealth, a tech company founded in 2016 by former Israeli Air Force pilot Eran Orr, aims to dramatically expand VR’s role. Orr was inspired to establish the firm in Tel Aviv after undergoing rehab for whiplash sustained during his service as an F-16 pilot.

Today, VRHealth has offices in Tel Aviv and Boston, with plans to expand to London in the coming years. Its software – which runs on the Oculus Go VR platform – has CE Mark and FDA approval as a medical device, and is available in the US, Europe, Israel and Australia across several indications.

“We have applications for physical therapy, cognitive rehab, pain management, hot flashes,” says Orr on the phone from the company’s Boston office. “We see VR as a toolbox for different indications.”

Physicians can track the patient’s real-time performance and progress.

Image courtesy of VRHealth.

Therapy and pain management: the VR toolbox

VRHealth’s applications take the form of virtual activities that users engage in while wearing a VR headset; these activities are designed to run patients through physical or cognitive therapy exercises while monitoring their performance in real-time so patients and their physicians can track their progress.

A particularly interesting indication that VRHealth is exploring is the use of VR for pain management. Chronic pain presents a tricky conundrum for health providers, as the source of a patient’s pain is often hard to track down physiologically, and the ongoing opioid crisis in the US and elsewhere has put into stark relief the risks of long-term treatment of pain through opiates and other strong painkillers. VRHealth presents its technology as a potential alternative to pharmacological pain management through nothing more than immersive distraction.

VRHealth presents its technology as a potential alternative to pharmacological pain management.

“Our brain is like a CPU – 75% of that CPU goes to visuals and sound,” says Orr. “When we overload our CPU with an immersive technology like VR, things like pain can get downgraded in the priority list. That’s why it’s amazing for pain management or pain distraction. Once you combine that with actual rehab, physical therapy or any other process where pain is another element, it’s a game-changer.”

Orr relates the story of a recent client with recurring migraines, who the company persuaded to trial its software before committing to long-term pain relief drugs.

“She just texted me yesterday that she can’t believe how powerful it is, and how effective the therapy was,” he says. “I believe in the next couple of years, we will continue to see more and more cases like that, and we will see VR being adopted as a replacement for opiates and different kinds of pain relief medication, because it’s very powerful with no side effects. I think, and I’ve said this to various executives here in the US, we will find that VR is the solution to the opioid crisis.”

Creating fun and engaging VR activities can boost the enjoyment for patients. Image courtesy of VRHealth

‘Gamification’ and remote healthcare

Setting up VR as a future replacement for opiates is certainly a bold claim, and the jury remains out. But the power of VR and the ‘gamification’ of therapy goals is becoming increasingly apparent – creating fun and engaging VR activities that patients will enjoy coming back to – whether it’s ‘Balloon Blast’ for shoulder range of motion or ‘Color Match’ for motor cognitive training – has obvious implications for compliance, but Orr says it goes further than that.

“We have patients coming to their physical therapy, in this case, saying that they can’t move their arm or their head because they’re in pain,” he enthuses. “Once they put the VR headset on, they forget all about it. We’ve even had family members taking photos of their loved ones from the outside to prove to the patients that this is what they did while they were in the virtualised world. That’s the amazing power of gamification, and the combination of gamification and virtual reality. Because they want to beat their goal, or to win in that specific game.”

While patients can focus on enjoying the games and meeting their therapeutic goals, the back-end of VRHealth’s software generates huge amounts of performance data for analysis, and the VR format makes for a unique source of insight.

It’s not like any other wearable device because we can control the environment.

“Every time someone puts the VR headset on, he becomes an element in a computer-generated environment,” says Orr. “It’s not like any other wearable device because we can control the environment. With a 2D screen, you can never know what happens until that patient interacts with the 2D screen. That’s one of the problems with cognitive assessment. But with VR we can see if the patient hesitated or not, if he was disoriented. Before he actually interacts with the virtual objects, we can analyse the entire sequence that happened before.”

In January, VRHealth announced that it had collaborated with the American Association of Retired Persons’ Innovation Lab to launch a telehealth platform allowing patients to go through their VR therapy at home, while the resulting data can be accessed remotely by their doctors. At a time when healthcare access is a concern in many markets, this is another option for patients who might struggle to reach the clinic or hospital.

“It makes location meaningless,” says Orr. “As we see it, the first time you encounter [the VR tech] it should be in a controlled environment, but from that point on you’ll be able to do everything remotely back home. Long-term, we think most of the usage will be at home, where people will put the VR headset on, and all the data will be analysed as part of your rehab.”

Enhancing VR’s credibility in healthcare

That’s VRHealth’s sales pitch, in any case. As with any new technology entering a market as rigorously regulated as medical devices, it will take some time to convince sceptics that VR is more than a gimmick.

“I think VR as a technology, and the fact that it has been hyped for the last four years – that has put us in a challenging position, because people still believe that VR is just for gaming, and it’s like 3D televisions – something that will go away, a gimmick,” Orr says. “But I think that more and more people understand the potential of VR specifically in healthcare. We’ve seen a change in the last six months.”

More and more people understand the potential of VR specifically in healthcare.

One issue is the relative lack of high-quality evidence that VR therapy provides clinical benefits above and beyond its more traditional counterparts. Orr says the company is conducting 14 clinical trials in parallel in the US, Israel and Canada to generate results that the company hopes will validate its approach, although it’s clear that Orr himself puts the highest value on the ongoing day-to-day experiences of the company’s users across the 30,000 sessions logged on the software so far.

“At the end of the day, for anyone who reaches out to us – any clinician or patient – the best way for us to convince them that this is a game-changer is them trying it out. That’s what I say to everyone. Take one headset, one platform, and try it out for a month. Now let’s talk.”