Feature

Venezuela’s migration crisis and a Colombian ‘Smart Clinic’

President Maduro is driving millions of Venezuelans to migrate along routes littered with danger and disease. By Alex Blair.

The Simon Bolivar International Bridge, the main gateway for migrants crossing from San Antonio del Tachira, Venezuela, to the Norte de Santander province of Colombia. Credit: George Castellanos / Getty Images

"If one of my children gets sick, all three get sick. Sometimes, my boy would cry, asking for food but there was none. It was despair. There was not enough money.”

Yelimar’s story is one of 7.7 million. A Venezuelan migrant and mother of three, Yelimar was forced to flee her homeland on foot with her partner Víctor and children Abraham (one-year-old), Mia (three) and Víctor (four) – a perilous journey documented by the Interagency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants (R4V), an international organisation coordinating the response to the Venezuelan migrant crisis.

Having passed demands for money from opportunistic Venezuelan police officers along the trochas (informal routes) set up near the Simón Bolívar International Bridge, the main gateway between Colombia and Venezuela, migrants (or caminantes) must traverse the formidable Berlin plateau separating them from Bucaramanga, the first major Colombian city.

Paths then diverge. Many migrants head south to Bogota and Medellin, or further afield to Ecuador and Peru. Between January and June this year, 122,616 Venezuelan caminantes travelled north to brave the notorious Darien Gap, a 96km-wide stretch of dense rainforest separating Colombia and Panama, aiming for Costa Rica, Mexico or the US.

Caption. Credit:

Numb feet, bleeding legs and dehydrated bodies mark their journeys – not to mention infectious diseases and psychological trauma. Studies have identified outbreaks of measles, diphtheria and malaria across Venezuela, while tuberculosis, typhoid and HIV, are also resurgent.

PTSD to unwanted pregnancies: treating Venezuela’s caminantes

Caminantes are generally at greater risk of communicable diseases because of the inadequate access to food, water and sanitation on the long, exhausting journeys they endure, according to Francisco Vélez, managing director of Siemens Healthineers Colombia.

“A large group of Venezuelan migrants and vulnerable populations in the north of [Colombia] do not have access to health,” Vélez tells Medical Device Network. “Many of them must travel several kilometres in very difficult conditions to be able to access these basic services.”

Recent border monitoring surveys reveal that 54% of refugees and migrants in transit through Costa Rica and 46% in Mexico reported needing healthcare during their journeys, according to International Organisation for Migration (IOM) figures shown to Medical Device Network.

In Peru, 23% of migrants and refugees in transit expressed an urgent need for care, while, in Colombia, 26% of migrants required healthcare services. 36% of them were unable to obtain the care they required.

For instance, those arriving in Panama after navigating the Darien Gap “frequently encounter serious physical and mental health issues”, says an IOM spokesperson. “This includes specific health needs for individuals who have suffered sexual assault during their transit.”

Measles, foodborne and waterborne diseases are also major risks for caminantes, as are hypothermia, burns, unwanted pregnancy and delivery-related complications.

Alongside children, pregnant or lactating women are the primary target group of Siemens Healthineers ‘Smart Clinic’, which provides free health services in remote parts of northern Colombia.

The Smart Clinic – a 12m-long bus equipped with “state-of-the-art medical devices” including x-rays and ultrasound – aims to “facilitate access to basic and specialised healthcare services for vulnerable and migrant populations”, Vélez says.

The Smart Clinic in La Guajira, Colombia. Credit: Siemens Healthineers

30 employees from the Colombian Red Cross and government operate the Smart Clinic’s services, which include paediatrics, gynaecology and orthodontics. The Smart Clinic also offers psychological check-ups, a crucial service as migrants are likelier to suffer major depressive disorder (MDD), generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than host populations.

At the start of September, R4V launched its most recent Refugee and Migrant Needs Analysis, which “covers the health situation of Venezuelans refugees and migrants in destination countries and in transit”, a spokesperson for the UNHCR, the United Nation’s refugee agency, tells Medical Device Network.

In the analysis, R4V data shows that 2.8 million Venezuelan migrants have arrived in Colombia over the last six years.

As many have “limited access to health services”, Vélez adds, “the Smart Clinic was designed to help provide primary health care services to the population in conditions of high social vulnerability in communities of Atlántico and La Guajira, in northern Colombia”.

Since 2020, the Smart Clinic has treated more than 29,600 patients across 23 Colombian municipalities – 19 in the departamento (state) of Atlántico, and four in Venezuela-bordering La Guajira.

While Smart Clinics are currently operating in Jordan, Iraq and Egypt, the Colombian Red Cross and Siemens Healthineers have deployed just one mobile healthcare unit in Colombia “for the moment”.

“This solution is absolutely scalable, and different actors in other countries are interested in the solution, but there’s nothing clear at the moment,” Vélez concludes. “It is not in the plan to go into Venezuela at this point.”

Siemens Healthineers’ comparable revenue growth of between 4.5% and 6.5% for 2024 certainly leaves fiscal room to invest in another Smart Clinic for Colombia.

Lenus Capital Partners, which became one of Colombia’s major healthcare providers last year when it acquired the Medicadiz Hospital in Ibague, could also prioritise funding and resources for the treatment of Venezuelan caminantes.

As Venezuela’s hospitals implode, Colombian healthcare strains

Local NGOs and international humanitarian organisations are trying to plug the gap.

From Pamplona, north-east Colombia, On the Ground International supports Venezuelan caminantes crossing the border into Colombia – providing meals and refuge at various shelters, or transporting supplies for migrants on the way to Cucuta or La Laguna.

The IOM, meanwhile, has trained more than 45,000 health sector officials in Colombia to provide care for migrants, as well as donating 800,000 biomedical supplies and equipment since 2018.

On The Ground International assists Venezuelan caminantes (pictured) between Pamplona and La Laguna, Santander, Colombia. Credit: On The Ground International / Facebook

Despite such efforts, Colombia’s healthcare system continues to struggle with the demand of its own population, let alone millions of migrating Venezuelans.

Gustavo Petro, Colombia’s first-ever leftist President, has promised health reform, delivering a series of proposals aimed at expanding primary care, training health workers and strengthening hospital infrastructure.

Petro’s reforms saw Colombia’s National Superintendency of Health (Supersalud) place the country's two largest health insurance providers, Entidades Promotoras de Salud (EPS) Sanitas and Nueva EPS, under government control in April 2024.

But political resistance and financial realities mean large swathes of rural Colombia, South America’s second most populous country after Brazil, remain underserved when it comes to healthcare.

The Colombian state is responsible for paying hospitals for costs related to emergency care for migrants. Payouts are very slow, however, meaning hospitals have little inclination to attend to undocumented Venezuelans, or if they do, they charge migrants directly.

Such policies meant Venezuelans infected with the Covid-19 virus could not get medical care – or were held in Colombian hospitals by private security until reaching agreement on payment.

For Venezuelans caminantes, however, Colombia’s strained healthcare system and the dangerous journeys they endure are far from a deterrent compared to the dire economic, political and medical landscape back home.

“The hospitals in Venezuela lack nurses, and they lack many resources”, says Carla, a Venezuelan migrant in Tibú, Colombia.

Common medical supplies to assist with childbirth are in scarce supply in Venezuelan hospitals – let alone artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), hydroxychloroquine, primaquine or other antimalarial medicines.

“20% to 40%” of Venezuelans promise to leave if Maduro holds onto power

Substandard healthcare is far from the only factor driving the largest recorded displacement crisis in the Americas.

The electoral fraud of incumbent President Nicolás Maduro has exacerbated Venezuela’s already extreme state of economic and political turmoil.

Following Venezuela’s elections on 28 July, Maduro yet again declared himself victorious despite voters appearing to have overwhelmingly voted for change in the form of banned opposition leader María Corina Machado and her replacement candidate, Edmundo González, who has fled Venezuela to seek political asylum in Spain.

Independent vote counts estimate González received up to 67% of the vote, compared to Maduro’s 30%.

María Corina Machado and Edmundo González lead an opposition protest against Maduro's declared election victory in Caracas, Venezuela, on 17 August, 2024. Credit: Jesus Vargas / Getty Images

In response to international pressure to release electoral data, Maduro and his allies have mobilised specialist military units to Caracas, launching a campaign of human rights abuses and digital authoritarianism.

Authorities have made 1,673 arbitrary detentions (as of 9 September) since the election, data from Venezuelan pro bono legal service Foro Penal shows. There have been more than 17,500 political arrests since Maduro took power in 2014.

Such repression has driven even more Venezuelans to migrate as “one of the coping strategies” to the crisis, in the words of Victor Aguilar Pereira, senior officer for Latin America and the Caribbean at International Crisis Group.

“If Maduro remains in power, migration will certainly continue or even increase, at least for some time,” Pereira tells Medical Device Network. “According to different public opinion polls conducted before the election, between 20% to 40% of those surveyed answered that they would consider leaving the country if Maduro won.”

As by far the most common destination for Venezuelan migrants, Colombia’s healthcare, humanitarian and asylum systems are set to face even greater strain. Peru, Brazil, Chile and Ecuador will be the other countries in the region most affected.

Venezuela’s economy is expected to deteriorate even further if sanctions from the US and other nations remain, or new ones are adopted.

While the US holds the most diplomatic sway, leftist Latin American leaders with open communication channels to Maduro’s administration – namely Petro and Brazilian President Lula – should exert pressure by “publicly stating that they won’t recognise the election results and warning that this could create a power vacuum by January 2025”, says Facundo Robles, Latin America programme coordinator for US thinktank the Wilson Center.

“In Washington’s case, beyond symbolic measures like seizing Maduro’s presidential plane, a more strategic approach is needed,” Robles tells Medical Device Network. “The US should focus on systematically sanctioning or isolating key decision-makers within Maduro’s inner circle, which could create fissures within the regime and possibly open avenues for negotiation.”

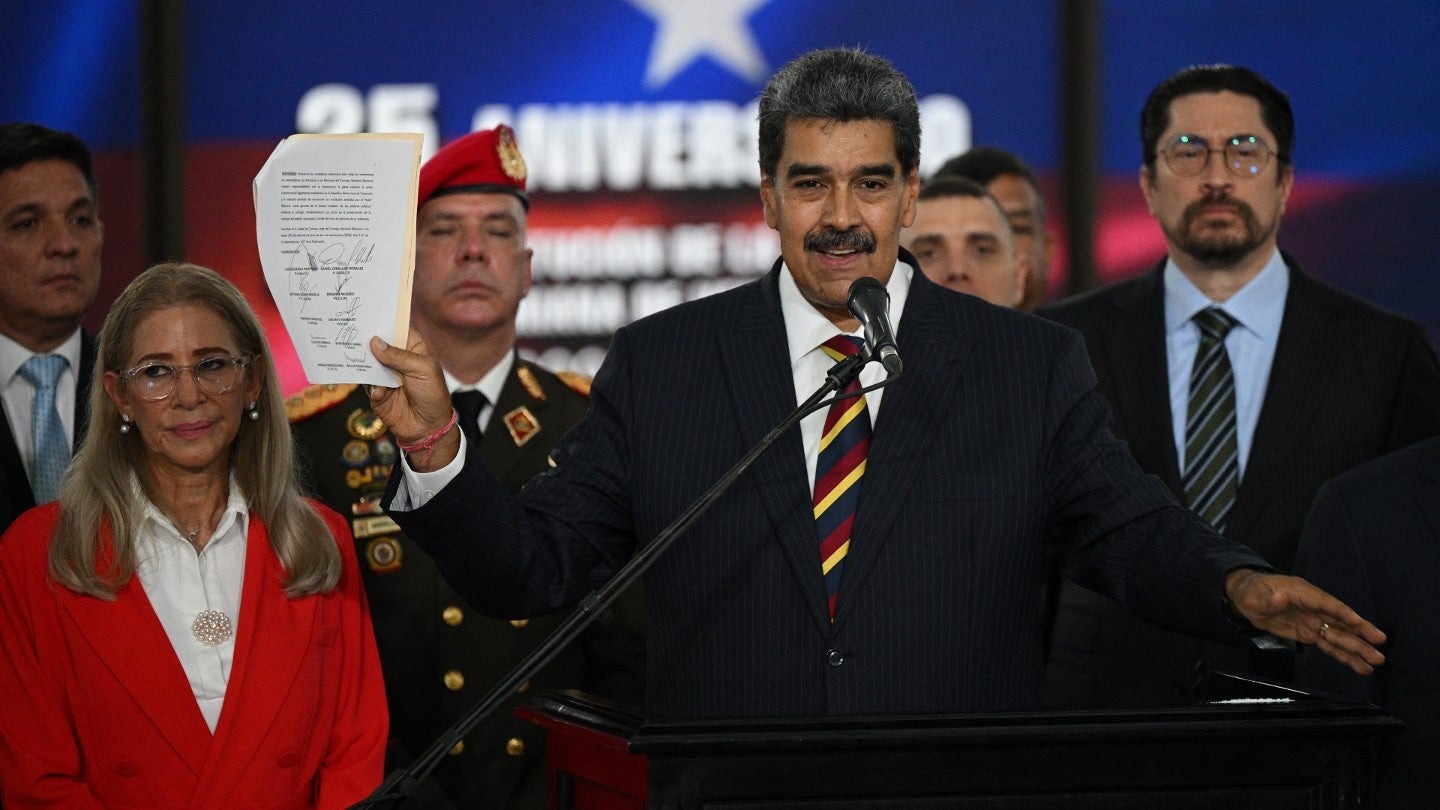

Nicolás Maduro brandishes a document with the signatures of recognition of the presidential election results, after appearing before the Supreme Court of Justice in Caracas on 9 August, 2024. Credit: Federico Parra / Getty Images

This regime has left Venezuela, once South America’s richest country with the largest proven oil reserves in the world, unfathomably poor, depriving its inhabitants of healthcare provision and driving them to flee to perilous situations.

“I think the international community has to consider putting economic pressure on the Venezuelan regime and its members and really go after a lot of their ill-gotten gains,” Carlos Trujillo, former ambassador to the Organisation of American States (OAS) during the Trump administration, told Medical Device Network's sister publication Investment Monitor in August.

“Their playbook is to use the SEBIN [Venezuelan intelligence agency], use the colectivos [informal, government-backed armed gangs], use all their non-traditional criminal groups to start harassing, intimidating, kidnapping and eliminating the opposition. They can’t beat them in the ballot box, so they’re only going beat them with their bullets.”

Amid such unrest, the welfare and survival of Venezuela’s millions of caminantes will be easily overlooked.

Once we see where those changes are, we can plan where we’re going to cut the bone.

Dr Lattanza

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.