Manufacturing

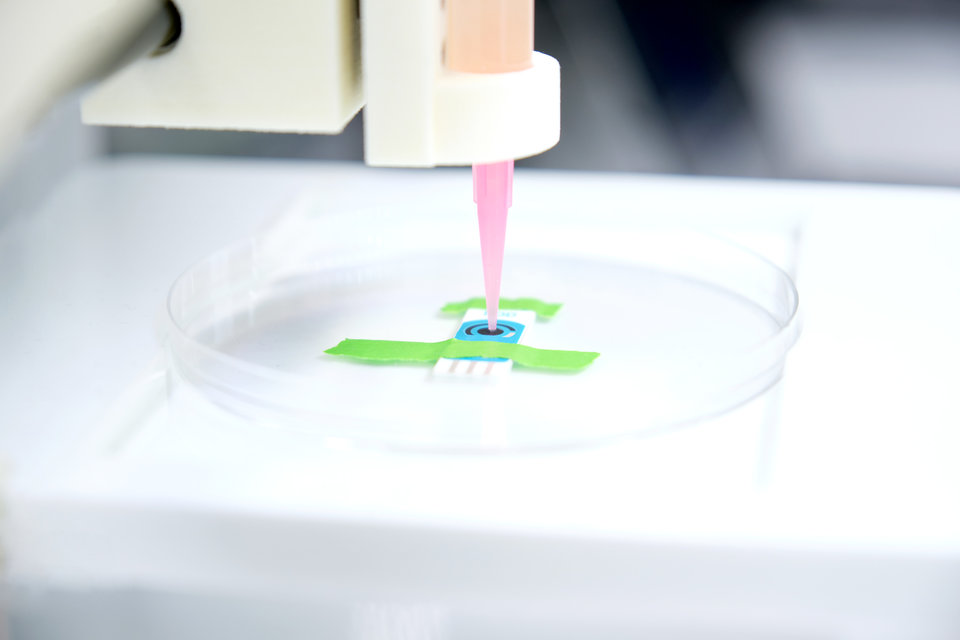

3D printing devices on site: healthcare hero or hazard?

The FDA is seeking public feedback on the 3D printing of medical devices at healthcare facilities to assess regulatory needs. Abi Millar explores the potential of 3D printing at the point of care and the challenges involved.

W

hen used at the point of care, 3D printing allows for personalised medical devices and implants to be manufactured almost at the patient’s bedside. This might be a customised prosthetic limb, an orthopedic implant, or a patient-matched anatomical model used to plan surgery.

In other words, the technology could make one-size-fits-all devices a thing of the past. Production would be quick and inexpensive. And because it takes place in the hospital itself, you could effectively eliminate the gap between healthcare provider and device manufacturer.

“It can also promote collaboration and innovation,” say John Fuson and Hilary Johnson, lawyers at Crowell & Moring. “For example, 3D printing at the point of care can allow physicians to work directly with engineers doing the manufacturing itself, even in real time, to generate solutions and ensure that the manufactured device functions as intended.”

However, as with all new technologies, it is wise to proceed with caution. While the technology is spreading rapidly across the medical field – as of 2020, there were over 100 hospitals in North America with a 3D printing facility – there are still some questions that need asking.

“The primary concern is that, when manufactured by healthcare providers that have limited experience using the technology, 3D printed products could harm patients,” says Liz Richardson, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ health care products project. “Stronger regulations can help alleviate those risks, but the FDA still has a long way to go on this front.”

In fact, watchdog ECRI has flagged up 3D printed medical devices as one of its top health technology hazards of 2021. As ECRI points out in a recent report, if a 3D-printed personalised device is created without the appropriate checks in place, it may not perform as intended. This in turn could lead to procedure delays, surgical complications, infection or patient injury.

The regulatory challenges

Since 3D printing is an emerging technology, regulation remains a work in progress. In December, the FDA published a discussion paper on the subject, which lays out the benefits and challenges and provides a potential approach for regulatory oversight.

“The release of this discussion paper is intended to foster discussion and solicit feedback from the public,” said William Maisel and Ed Margerrison of the FDA. “This feedback will help build the foundation for an appropriate regulatory approach for 3D printing at the point of care, personalised care for patients and new innovations in this area.”

The document runs through three potential 3D printing scenarios that may arise and points out areas where stakeholder feedback might be useful. It notes that the extent of oversight should correspond with the actual risks, which vary depending on the device in question.

For instance, a hospital may be capable of 3D printing some devices but not others, while other devices might be wholly unsuitable for manufacture at the point of care.

In some 3D printing scenarios, the distinction between medical device and medical practice is unclear, so the regulations pertaining to health care facilities can also end up being ambiguous.

“The existing regulatory framework will likely need to adapt to account for point-of-care manufacturing, and it’s clear that the agency is still thinking through what those changes will look like,” says Richardson.

“The factors FDA needs to consider include the type of products that hospitals may manufacture at the point of care, what regulatory requirements they should be subject to, and the best way for the agency to enforce those requirements to ensure that products are safe and effective.”

She remarks that the document answers some, but not all, of these questions. This is a complex area, complicated further by the fact that the FDA does not directly regulate the practice of medicine. (Here, the job falls primarily to state medical boards.)

“In some 3D printing scenarios, the distinction between medical device and medical practice is unclear, so the regulations pertaining to health care facilities can also end up being ambiguous,” says Richardson. “The agency may also experience challenges in determining how to deploy its limited inspection and enforcement resources.”

With regard the latter point, Richardson thinks the FDA may need to consider partnering with hospital accreditors or professional bodies involved in 3D printing, to help bridge the gap in oversight.

Why we need more clarity

From a legal perspective, choosing to 3D print their own medical devices may bring challenges hospitals aren’t used to facing.

“Healthcare facilities, which are typically focused on patient care, are likely most familiar with medical malpractice litigation,” say Fuson and Johnson. “But healthcare facilities who opt to perform their own 3D printing rather than outsourcing it to a traditional manufacturer may become targets of medical device product liability litigation, an extremely active litigation space.”

They add that point-of-care printing arrangements can cause hospitals to blur the lines between traditional manufacturers and healthcare providers. As a result, many traditional product liability defenses won’t apply.

This means some regulatory clarity is sorely needed. Fuson and Johnson hope that FDA will be able to leverage existing controls without applying too much red tape and over-burdening manufacturers.

3D printing could potentially improve patient access to devices and treatments tailored to their unique medical needs, and by extension improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

“Current regulations may impose stringent or even duplicative requirements in some circumstances,” they say. “FDA appears to recognise these issues and to be appropriately focused on regulating based on broader principles, such as applying a risk-based approach and ensuring the consistency of the end product.”

As Fuson and Johnson see it, patients, providers and manufacturers should all take advantage of the opportunity to comment on the FDA’s paper. After all, they’re the ones best placed to understand the practical considerations that may impact them.

Richardson adds that, since 3D printing also has possible applications in product areas outside of devices – think 3D-printed pharmaceuticals and bioprinted skin grafts – there is a lot more work to be done in terms of developing guidance documents. Innovation, however exciting, must be balanced against oversight.

“3D printing could potentially improve patient access to devices and treatments tailored to their unique medical needs, and by extension improve patient outcomes and quality of life,” says Richardson. “But regulatory oversight must evolve alongside innovations in the technology to ensure that the benefits outweigh any risks to patients or to public health.”