Clinical Trials

Human + machine: The future of digital healthcare

At the recent Medidata NEXT conference, Ronan Wisdom, global lead at Accenture’s Connected Health practice, discussed new forms of human-machine collaboration and their potential impact on healthcare and clinical development. Susanne Hauner reports.

"W

e're entering an age of human empowerment, where technology will augment humanity and fundamentally improve the way we live and work,” Accenture’s global lead for connected health Ronan Wisdom told delegates at the Medidata NEXT conference in New York in October.

Wisdom’s keynote was titled ‘Human + Machine’. The plus symbol, he pointed out, was significant in describing emerging applications of artificial intelligence (AI), which Accenture believes will appear in the form of collaboration between humans and intelligent machines.

He identified three key trends that are driving innovation in human-machine collaboration: “The first is the growth of smart devices and smart products,” he said. “The second is new forms of interaction with those devices and the third is new forms of AI that are underpinning everything. And we think the combination of those three advances are going to change the opportunities for research across industries - healthcare included.”

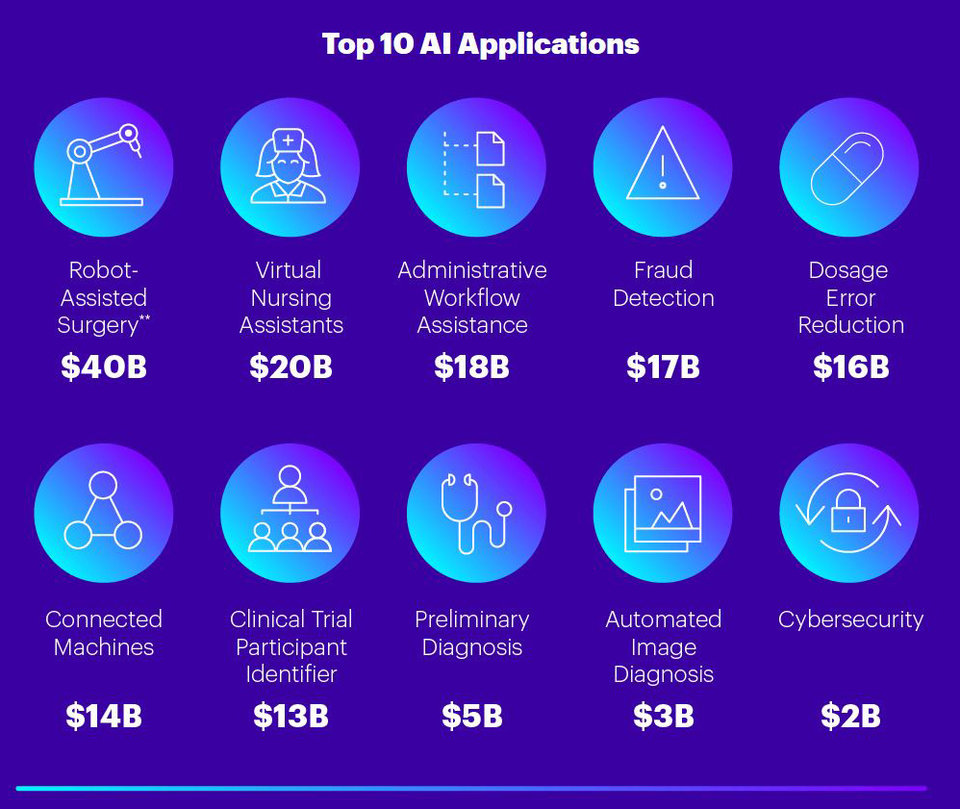

The top ten applications of AI in healthcare and the value they will produce to 2026, according to Accenture’s forecast. Source: Accenture analysis

Smarter devices create new healthcare applications

Connected health devices are moving beyond wrist-worn trackers and becoming clinically relevant and medically accurate. This allows for new forms of health monitoring – for example, tracking disease progression by monitoring behaviour and cognitive function with smart clothing. Other recent examples include digital pills and injectable nano devices designed to function as biomarkers.

But beyond that, everyday objects are also becoming smarter and more connected, which Wisdom argues gives them new potential for healthcare applications.

“I'm not talking about a smartphone, or a connected health wearable, or a regulator device,” he explained. “I'm talking about everyday objects that we interact with – smart cameras, household appliances, cars and so on. Those objects are getting really, really smart and we think they're going to play an increasing role in our healthcare.

The mirror we use in the morning can detect changes in skin condition and eye health. The bed we sleep in at night can detect sleep patterns, interruptions and body temperature.

“Do we think the digital health of the future will be bound by our smartphone and a wearable?” he asked. “When the mirror we use in the morning can detect changes in skin condition and eye health. When the bed we sleep in at night can detect sleep patterns, interruptions and body temperature.

“When a car, understanding that we're diabetic and having access to our connected glucometer data, can analyse our driving patterns, maybe the composition of our sweat, and warn us that we're at risk of an impending hyperglycaemic event. When the bus shelter that we stand at waiting for a bus is not only measuring air pollution, it's listening for coughing to detect the potential spread of infectious disease.

“I'm not kidding with that one. It exists and it's out there.”

In addition to these potential end user applications, Wisdom explained, such smart everyday objects will also create new data and insights that could help to inform clinical research.

The changing nature of human-machine interaction

The second driving trend Wisdom identified in AI applications is the development of new forms of interaction between humans and machines. Conversational interfaces are just one example that could impact healthcare in a number of ways, ranging from operational through assistive, into advisory and clinical.

On the operational side, that includes automating parts of the administrative workflow, for example voice-to-text transcriptions, while assistive systems are usually designed to support patients, for example through automated chat interfaces. The significant leap, Wisdom believes, lies in the advisory category, because it requires a more sophisticated AI than operational and assistive services.

“An advisory service has to know us as a patient for much longer time,” he explained. “It has to build a profile based on us, based on our preferences, but also based on our behaviours and activities. It has to be able to filter content based on our preferences, suggest new content and options and watch over us for harm in terms of making decisions.”

Beyond the quantitative nature of what a patient might say to a conversational machine, we're really interested in the qualitative nature of what's said - the behavioural aspects of how we speak.

As an example of assistive technology application that combines smart objects, new forms of interaction and AI, Wisdom showcased the Drishti app, which was developed by Accenture’s Tech for Good programme to help the visually impaired make sense of their surroundings.

This video from Accenture shows the Drishti app in action.

Aside from their use in assistive healthcare applications, Wisdom noted that conversational interfaces also have potential in clinical studies.

“Of course for electronic patient-reported outcomes it makes obvious sense, but beyond the quantitative nature of what a patient might say to a conversational machine, we're really interested in the qualitative nature of what's said - the behavioural aspects of how we speak. Turn-taking, repetition, interruption, frustration, emotion - all of these factors create a vocal biomarker that we can use to assess whether a patient is engaging with a service, whether they are likely to drop out of a service, and this is really relevant when we think about challenges in clinical.”

Making AI work for clinical purposes

Although AI has existed since the 1950s, it’s only in the past five to seven years that new forms of machine learning have empowered applications such as computer vision, making them penetrative from a commercial perspective, Wisdom said.

These advancements are reflected in the levels of funding received by the AI community overall, as well as data science and AI startups – a trend that is particularly relevant in life sciences and healthcare.

However, Wisdom says, there is a missing link in the human + machine equation which needs to be addressed.

“We call it collaborative intelligence, he explains. “If you think about what a human is good at – articulation, communication, improvisation, generalisation – and what a machine is good at – repetition, memorisation, prediction – we need new ways to bring those two ends together to unlock new value. And we think there's a lot of opportunity in that middle space to create new solutions that are based on collaborative intelligence.”

I'm not suggesting that smart objects and new forms of interaction and new AI necessarily go directly to support new endpoints.

So to what extent will these developments in AI transform clinical research?

“I'm not suggesting that smart objects and new forms of interaction and new AI necessarily go directly to support new endpoints,” Wisdom said. “But do I think that they can increase participation and diversity for people like you saw in the DRISHTI video, who have impaired vision or are blind, by enabling them to participate in a virtual trial? Absolutely!

“The reality is, there's competition in the ecosystem. Sponsors are vying for some of the same investigators, and those investigators are advocating for their patients' health. And one of the questions they ask is: who has the best technology?

“And that means the molecule, yes; but it also means the technology surrounding the design and execution of the trial, and the ability to remove obstacles and challenges, improve engagement, and improve participation and diversity.”